How Personalized Health Can Extend your Lifespan

Daniel Zahler on how technology can help us find the optimal diet to promote personalized health

A few weeks ago I attended my first in-person medical conference since Covid: the annual Health Leaders of New York Mini-Congress.

I was excited to connect with healthcare leaders. I miss the spontaneous interactions that happen when you bring smart people together in a room to solve problems.

Networking is harder when everyone wears masks. But I enjoyed the event.

One highlight was a panel discussion called “Technology Innovation Changing the Face of Care Delivery.” I saw my old McKinsey colleague, Kevin Kumler, US President of Virta Health, speak about his company’s mission to reverse type 2 diabetes.

Virta Health provides personalized diet plans to reduce insulin resistance, the primary cause of type 2 diabetes. The software delivers advice and coaching via a mobile app or website.

A clinical trial with 350 patients showed the Virta Health personalized diet program reversed type 2 diabetes in a majority of patients. Virta patients lose over 30 pounds on average within the program’s first year.

I was impressed with Virta’s results. Getting people to change their diet is hard. Every week we get conflicting guidelines on what’s healthy and what’s not.

I wondered: How can technology help us find the optimal diet to promote health?

The “holy grail” of wearables

People respond differently to certain foods. Yet we rely on a one-size-fits-all approach to diet and nutrition: Eat this, don’t eat that.

Can we do better? New technologies have emerged to help us understand how our bodies respond to food.

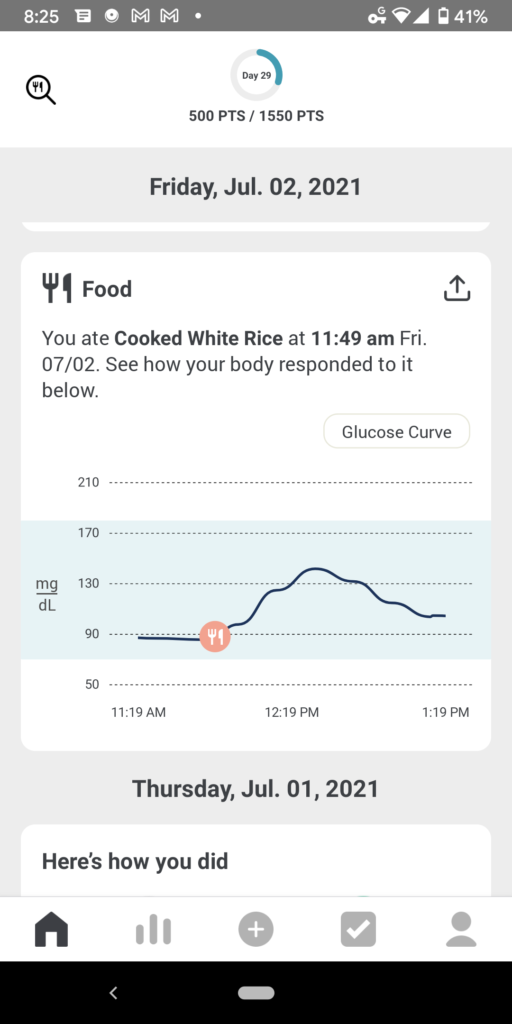

More people are using a continuous glucose monitor (CGM). Commonly used by diabetics, it tracks glucose rates in real time via a microneedle installed in the upper arm. Companies are building apps that pair with these CGMs and tell you in real time which foods spike your blood sugar.

A company called Graphwear recently raised $20 million to make CGMs that use nanotechnology to measure blood glucose levels, using a needle-free version of the device.

The next-generation Apple Watch may have sensors that let users measure their blood glucose level, according to a new report.

Continuous glucose monitoring is the holy grail of wearables, says Dr. Daniel Kraft, a Stanford & Harvard trained physician-scientist. It could be a game-changer for millions of people.

Rumors of continuous blood glucose monitoring (the holy-grail of #wearables) for future #AppleWatch versions continue.

— Daniel Kraft, MD (@daniel_kraft) October 25, 2021

I’d expect CGM as well as blood pressure by 2024.

A powerful #DigitalHealth combo, combined with current sensors & analytics…https://t.co/O4CzKRUuX6

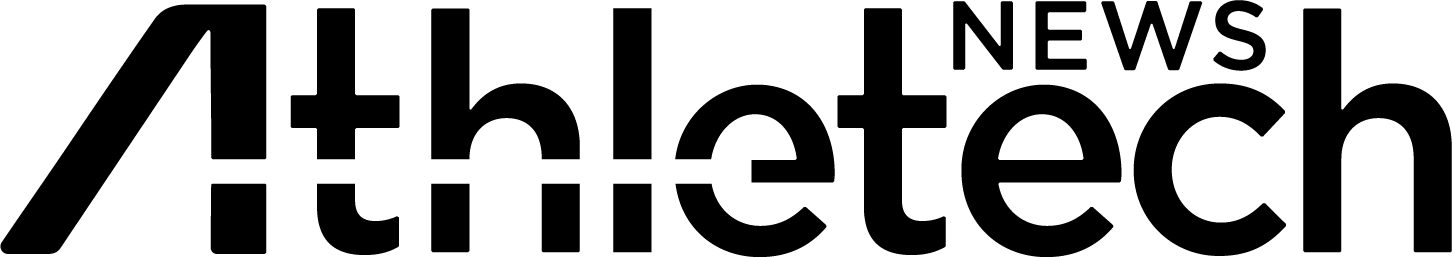

The problem: Nutrition and medicine are disconnected

Experts see nutrition as a huge gap in healthcare. Doctors don’t get much nutrition training in medical school. Healthcare systems don’t have good tools for tracking and managing patient nutrition—even though it’s an essential part of health.

The good news: Technology is helping close that gap.

A new approach to metabolic health

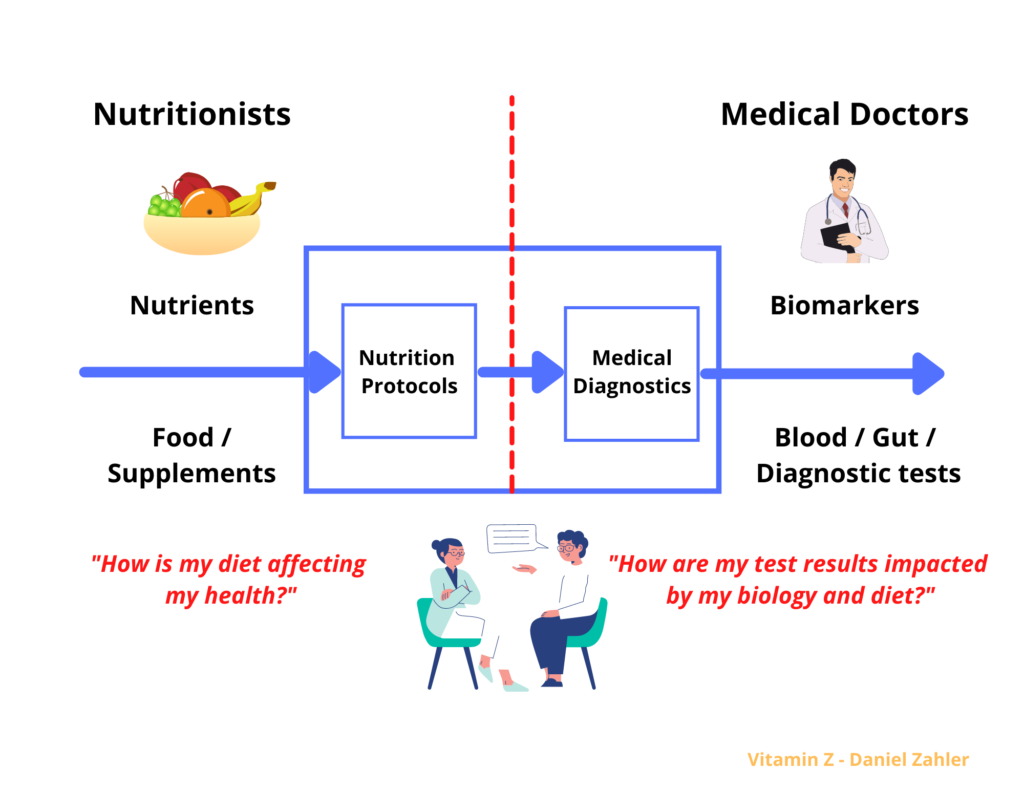

I spoke with Dr. Casey Means, co-founder and chief medical officer of Levels Health. The startup combines a wearable CGM with insight-driven software to show users how food and lifestyle choices are affecting health in real-time.

Levels Health is targeting nondiabetics and says it has a waiting list of 105,000.

Note: I’ve never used Levels Health personally and am not endorsing their products. You should consult a physician before using any of the tools mentioned in this article.

Dr. Means said:

“Levels gives members the ability to understand and track their blood sugar levels continuously as a window into their metabolic health. It’s like wearing a mini-lab on your arm, and is the first tool to create a closed feedback loop on nutrition. We’ve had wearables for feedback on fitness, sleep and stress, but never before for nutrition.”

She explained why CGM may be useful for non-diabetics:

“People often find that moving toward stable and healthy blood sugar levels improves many aspects of their current functioning, like sleep quality, energy, mood and athletic performance. The long-term goal of keeping blood sugar more stable is that it may reduce the risk of chronic metabolic diseases.”

Glucose is a real-time biomarker that’s affected by exercise, sleep, stress and food. Researchers have linked spikes in blood sugar, or glycemic variability, to increased mortality risk in people who aren’t diabetic. Yet more than 84% of the prediabetics don’t know they have the condition, according to the CDC.

Dr. Means said:

“Very little is normal about modern life. The majority of the food we consume is highly processed, we sleep fewer hours than we need, we experience chronic low-grade stress, and we move less than ever before. In the face of these realities, it can benefit us to have additional support to help us feel our best.”

A 2019 study found that people with type 2 diabetes who used CGM achieved an average 0.35-point larger reduction in hemoglobin A1c levels and had a lower risk of hypoglycemia compared with people who didn’t use CGM.

CGM devices are only covered by insurance for diabetics—not for the millions who are pre-diabetic or obese. For those willing to pay out of pocket, CGMs could become part of a solution for people battling obesity and metabolic disease.

Saying continuous glucose monitors are only for diabetics is like saying bathroom scales are only for the obese #wellness

— David A. Sinclair (@davidasinclair) July 14, 2021

Levels users say the system has helped them become more aware of added sugar and starches. Some are surprised to learn that when you eat white rice, your blood sugar spikes. Others have observed that stress changes how their body responds to food.

Dr. Means talked about the results people are seeing with Levels Health:

“Members are losing weight. We have a member who has lost 91 pounds using Levels. They’re getting better sleep, stabilizing their energy, improving their skin, seeing improvements in their hormones, better athletic performance, figuring out what to eat after years of trial and error, dropping their cholesterol and hemoglobin A1c, and more.”

For more information on metabolic blood tests, see this article on the Levels blog with insights from eight metabolic health experts. They explain the importance of testing for different types of cholesterol, C-reactive protein (a marker of inflammation) and hemoglobin A1c (a measure of glucose control and metabolic dysfunction).

How the microbiome impacts diet

We’re seeing a new generation of personalized health and nutrition apps that use AI to analyze a broad set of individual biomarkers and make recommendations.

Consider the microbiome—the vast constellation of microorganisms living in our gut. A study found that people can have dramatically different metabolic responses to the same foods, and that a person’s genetics, sleep, stress and exercise levels, and the diversity and types of microbes in their guts, all influence how they metabolize food.

A company called Viome lets you test what’s going on with your gut bacteria by sequencing your gut microbiome. Viome published a study of AI-powered diet and supplement recommendations based on molecular data from the gut microbiome. The study’s precision nutritional recommendations resulted in significant improvements in severe depression, severe anxiety, IBS, and type 2 diabetes risk.

Microbiome panels can also test for food allergies. They provide clues on food intolerance risks based on gut microbiota. For example, reduced levels of lactobacilli is correlated with milk and egg allergies. People with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) may benefit from a low-FODMAP diet.

Toward a future of personalized nutrition

Personalized health and nutrition have gotten a lot of hype in recent years. In most cases, the individualized nutrition solutions offered haven’t lived up to expectations. That may be changing with new systems that combine multi-sensor diagnostics and AI.

A company called January has derived the nutritional values for 16 million foods and dishes, including groceries, recipes and restaurant menus. They’re using analytics to personalize and predict an individual’s glycemic response to food.

I listened to an interview with January founder and CEO Noosheen Hashemi. She said:

“We ran a trial of one thousand people and associated people’s glycemic response to the foods they were eating. We turned this into a prediction model. This lets people compare foods. It can tell you, “If you eat this fried chicken, you’re going to have to walk 46 minutes afterward to put your blood sugar back into a healthy range.”

January uses a systems biology approach called precision health or multi-omics—defined as multivariate decision-making based on a wide variety of biomarkers: from cholesterol and hemoglobin A1c, to data from wearables that track physical activity, sleep, and HRV.

Ms. Hashemi said:

“If you eat nine days in a row, your glycemic response could be different each of those nine days because of how much you slept or how much fiber was in your body and whether you ate before bedtime.”

These offerings come at a steep price: $388 for January’s 90-day program and $399 a month for Levels. With the January system, you don’t have to wear a CGM every day; you just need to wear it a few times to get baseline readings. This kind of AI-powered solution could make personalized health and nutrition accessible by a much wider population.

Precision health is about disease prevention. It’s part of the transformation of medicine from a uniform, one-size-fits-all approach to one that reflects the massive complexity of human biology and the individual differences within us. We’re only just beginning to understand how our bodies work.

The hope is that by improving our understanding of how our bodies respond to food, we can take control of our biology decades before our first symptom. We’ll be able to shift intelligent decision-making from the healthcare system to the individual.

I’d love to hear your thoughts. Would you try using a CGM or personalized nutrition service?

This article was written by Daniel Zahler and first published on his Substack. Athletech News has Zahler’s permission to republish it here.

About Daniel Zahler:

Daniel writes about health and wellness trends, and strategies & tactics on how to optimize cognitive, physical and emotional health. He holds a JD and BA from Harvard, has worked at Goldman Sachs and McKinsey, and serves as a GLG council member advising global business leaders on healthcare innovation.